Soviet and Turkish voices in Berlinby Philip Greenspun |

Home : Travel : Berlin and Prague : Part 3

After a day of rest, I struggled over to Treptower Park's Soviet War

Memorial, a dignified square kilometer of sculpture and open space.

One enters through an arch ("Eternal fame to the heroes who fell for

freedom and the liberation of their socialist homeland") and walks

down a tree-lined avenue to a marble statue of Mother Russia.

Turn

left to two huge stone flags with 4m-high bronze soldiers in front and

a football field-size area in back.

("The Motherland will not forget her heroes")

After a day of rest, I struggled over to Treptower Park's Soviet War

Memorial, a dignified square kilometer of sculpture and open space.

One enters through an arch ("Eternal fame to the heroes who fell for

freedom and the liberation of their socialist homeland") and walks

down a tree-lined avenue to a marble statue of Mother Russia.

Turn

left to two huge stone flags with 4m-high bronze soldiers in front and

a football field-size area in back.

("The Motherland will not forget her heroes")

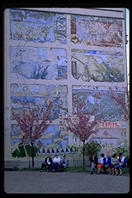

The football field has white stone slabs on the sides and an 11m-high statue at the far end (a soldier holds a child in one hand and spears a swastika with a sword held in the other hand). Each slab is edged with a quote from Uncle Joe and faced with relief sculptures of various phases of the war.

| The Germans attack |

| The Russians arm |

|

| The Russians fight back |

Under the big statue is a mausoleum with a socialist-realist mosaic surmounted with the words "today everyone recognizes that the Soviet people through its sacrificial struggle saved European civilization from the protagonists of the Fascist pogroms."

Although this monument was one of the most striking things I saw in all of Berlin, it was virtually untouristed. In fact, most of the West Berliners I spoke with had never heard of it. My hour at the monument was shared only by four older Russians and an English group, whose leader said "you are lucky to see it now because it will be gone in fifty years."

Anxious to see the German point of view, I stopped next at the Checkpoint Charlie museum, highlighting escape methods from Soviet-ruled East Germany. Newer rooms contain walls devoted to Gandhi in India and the struggle against Communism in the Warsaw Pact countries. At first these displays made sense to me, covering the common theme of "unwelcome guests in various countries." But then I wondered about the parallels that were being drawn. After all, the Czechs and Poles never planned to kill half the Russians and enslave the rest. I felt sorry for the 80 people killed trying to get through the Wall yet couldn't help thinking that it would have gone much harder for the Russians had Germany won the war.

In the evening, I joined a bunch of embassy staff for dinner in Kreuzberg, Berlin's Turkish/hip quarter. One of the diplomats spoke Turkish and had worked in our embassy there. Seen through his eyes, the neighborhood was astonishingly rich and peculiar. Many of the locals are super left-wing Turks or even Communist Kurds. Numerous signs supported Peru's Maoist Shining Path guerrillas. Someone had gotten up on a ladder and done a rather nice portrait of the recently arrested Shining Path leader in his prison stripes, 10m up the side of a building. Every little square was packed with Turkish families enjoying the warm evening. Children played together in the center and adults chatted on benches. Men wore Western suits, but their wives looked exotic in head scarves.

Once we stepped inside the restaurant, the Turks vanished to be replaced by long tables of raucous Germans laughing loudly and a bit drunkenly every 30 seconds or so. The menu was simple: roast chicken, roast chicken, or roast chicken. "Berlin is so interesting, you guys are really lucky to be stationed here, livin' large at taxpayer expense!" I remarked. "I like the city, but even after 15 years and speaking fluent German, I feel barriers with western Germans that I never felt with Italians, British, Turks, French, or Americans. Part of it is the smugness. For example, Germans will give you a long lecture about how much better they are at recycling than Americans. The truth is that their consumers are better but their industry is so much worse that the U.S. is better at recycling overall," noted an economics expert. "I've been having trouble dating here," complained a single fellow, "all the women look as though they just lost their best friend."

On the subway ride home I sat next to a really beautiful young woman with dark features and heavy silver jewelry. "Your English is remarkably good compared to most of the Germans I've met," I offered. "I'm not German. I'm Turkish!" she replied. "I was born here, but I'm not a German citizen. My passport is Turkish and that's true sometimes even for third-generation immigrants." Why couldn't she get a German passport? "Oh, the laws are Byzantine, but I could get a German passport if I wanted one. I don't. I don't have that much affinity for German culture, to tell you the truth, and even if I did, Germans would never accept me as German."

My last full day in Berlin was a Saturday and it underscored a lot of my

previous experiences in Germany. Stores can only legally open during

certain hours, mostly coinciding with the hours that people work. Thus,

the only time many people can shop is Saturday between nine and one.

Imagine midtown Manhattan on the Saturday before Christmas and you'll

have a fair idea of how crowded Berlin's main shopping district is every

Saturday. Shopping is a special case of a general principle: Only

one way of life is sanctioned in Germany. There are prescribed

times for shopping, eating, and working. Want to shop for a book after

6:30 at night? Drive to Switzerland. You'd like to have a late dinner?

Drive to France. Fancy buying ingredients for ethnic food? Fly to the

U.S. People who like the prescribed way of life find that everything is

convenient for them. People who don't want to live that way are often

unhappy and consider emigrating. I never fully understood why the

U.S. has the world's lowest rate of emigration. Italy and France, for

example, oftentimes seem like nicer places to live. [In 29 years I've

only met one American who expressed a genuine preference for longterm

life overseas and I love his reason. He once read a survey of Americans

who lived near airports. More than 80% of the people reported that

airplane noise bothered them when they were watching TV but only 10%

said that it disturbed them while making love.] In Germany, however,

the reason nobody leaves the U.S. hit me: it is impossible to be a

misfit in America. Each of us can choose a culture, climate, landscape,

working hours, shopping hours, etc.

My last full day in Berlin was a Saturday and it underscored a lot of my

previous experiences in Germany. Stores can only legally open during

certain hours, mostly coinciding with the hours that people work. Thus,

the only time many people can shop is Saturday between nine and one.

Imagine midtown Manhattan on the Saturday before Christmas and you'll

have a fair idea of how crowded Berlin's main shopping district is every

Saturday. Shopping is a special case of a general principle: Only

one way of life is sanctioned in Germany. There are prescribed

times for shopping, eating, and working. Want to shop for a book after

6:30 at night? Drive to Switzerland. You'd like to have a late dinner?

Drive to France. Fancy buying ingredients for ethnic food? Fly to the

U.S. People who like the prescribed way of life find that everything is

convenient for them. People who don't want to live that way are often

unhappy and consider emigrating. I never fully understood why the

U.S. has the world's lowest rate of emigration. Italy and France, for

example, oftentimes seem like nicer places to live. [In 29 years I've

only met one American who expressed a genuine preference for longterm

life overseas and I love his reason. He once read a survey of Americans

who lived near airports. More than 80% of the people reported that

airplane noise bothered them when they were watching TV but only 10%

said that it disturbed them while making love.] In Germany, however,

the reason nobody leaves the U.S. hit me: it is impossible to be a

misfit in America. Each of us can choose a culture, climate, landscape,

working hours, shopping hours, etc.

Whilst traveling in third countries, I'd had some difficulty understanding prejudiced anti-American statements I'd heard from so many young West Germans, but spending time here cleared up some of my confusion. First of all, older Germans from both East and West like Americans because they compare us to the Russians. For young West Germans, however, history starts when they became ten years old. Among the ones who've never been to America, there is a common laundry list of negative prejudices. America the land is an string of impoverished ghettos separated by vast distances of sometimes attractive scenery punctuated by wasteful, polluting and inefficient factories. Americans the people are too selfish to help the poor. Americans as people are ignorant of geography, culture, and cuisine. Americans are loud and shallow. We get no credit for never having started a world war, enslaved and plundered our part of conquered Germany, nor rolled over Canada and Mexico and sent their citizens to the gas chambers.

My epiphany came on this crowded Saturday: prejudiced Germans have only met American tourists in Germany. American tourists in Germany are in a bad mood because (1) the Germans around them are in a bad mood, (2) the bizarre opening laws leave them without essential items when they need them, (3) they can't get the variety of food they're used to, (4) the country is crowded, and (5) the prices are shocking. New Zealanders love every nationality because even people who are miserable at home catch the contagious national happiness there; Germans dislike many nationalities because even people who are happy at home catch the contagious national tension there.

Some German prejudices can't be explained by my pet theory. I looked up "USA" in a German encyclopedia once to see if that were the source of the German belief that Americans are geography ignoramuses. The first picture was captioned "USA: Morain Lake in Banff National Park in the Rocky Mountains" (for those of you whose geography is as bad as the Germans think, Banff is a good 250 km into Canada). The next night I encountered a well-educated 25ish German woman whose dream was to visit Siberia. I told her about my plans to drive to Alaska and she looked very confused. It turned out that she thought Alaska was an island in the North Atlantic.

Feeling uncommonly proud of myself for having developed so many brilliant insights and for having successfully done a little pre-Prague shopping, I dropped into the Egyptian museum to see the bust of Nefertiti. This is allegedly the finest thing ever to be hauled out of ancient Egypt. It was very fine and beautiful to the modern eye, which is impressive in something that old, but Egyptian stuff looks pretty forlorn when it has been ripped out of context.

Back out in front of the Schloss Charlottenburg I noted the huge line

of German tour buses--this is where all the people who don't visit the

Soviet War Memorial go. Jean and Carlos met me and we joined a guided

tour of this palace. It encapsulates official tourist Berlin rather

nicely. First, it is a mediocre copy of French styles and

concentrates more on quantity than quality. Second, most of its

original art, particularly the beautiful ceilings, were destroyed by

Allied bombs. Third, the only way to see it was an overlong tour

narrated ad nauseam only in German. The narration was so

boring that we tuned it out and chatted with Vera, a super-German

blonde, and Steve, her British boyfriend.

Back out in front of the Schloss Charlottenburg I noted the huge line

of German tour buses--this is where all the people who don't visit the

Soviet War Memorial go. Jean and Carlos met me and we joined a guided

tour of this palace. It encapsulates official tourist Berlin rather

nicely. First, it is a mediocre copy of French styles and

concentrates more on quantity than quality. Second, most of its

original art, particularly the beautiful ceilings, were destroyed by

Allied bombs. Third, the only way to see it was an overlong tour

narrated ad nauseam only in German. The narration was so

boring that we tuned it out and chatted with Vera, a super-German

blonde, and Steve, her British boyfriend.

Vera was about to forsake her native land to join Steve in London. As soon as she said this, the drama of the 1993 European unification hit me: one can simply decide to live and work in any country now without having to romance any bureaucracy. I asked Vera if she didn't mind leaving her native country. "I don't really like Germans or Germany. Besides, now is a good time to leave." Because of the economic downturn? "No, because of the political situation. There is so much tension between factions and I don't like the hatred of immigrants."

Vera was about the 50th German I'd met who had mentioned emigration and by then I had decided that the country was divided into two groups: people who could never fit in anywhere that wasn't exactly like Germany, and people who could never fit in anywhere that was too much like Germany. Members of the first group would be appalled to find that most American restaurants don't have special glasses for different kinds of beer. Members of the second group are exemplified by Dr. Anton, my companion from Heathrow to Stuttgart. Anton had worked in hospitals in New Zealand, England and Germany. "I'm emigrating to New Zealand in January because people die happy there. If they're 60 and get cancer, they don't mind dying because they've lived 60 good years. Sixty-year-old Germans struggle bitterly for life because they've never been happy." [Anton was also notable for his folk wisdom. A reference to a Black Forest girl with a heart of gold brought this response: Ein Mann ein Wort. Eine Frau ein Wörterbuch. ("A man a word; a woman a dictionary."]

We ate dinner at a pricey "Mexican" restaurant, with a choice of two quasi-Mexican dishes and 20 beers. Then we decamped to a party attended by a surprising number of South Americans of German descent. In a perverse twist on the U.S./England situation, they had come back to the Old World seeking economic opportunity. They reminded me of the super-patriot American immigrants of the 1920s who loved the U.S. with their heart and soul (was it Irving Berlin who said he loved to pay income tax?). When they found I was American, they vented their rage on the subject of the U.S.'s new Holocaust Memorial. They vehemently concurred with the prevailing German opinion that it should have been balanced by another memorial to the wondrous achievements of the new democratic Germany. I quipped that they could donate one of their monuments to the victims of Stalinism but nobody laughed.